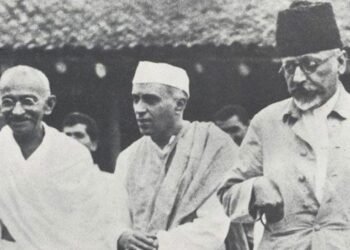

After Independence, Maulana Azad became India’s first Education Minister (1947–1958) in Jawaharlal Nehru’s Cabinet.

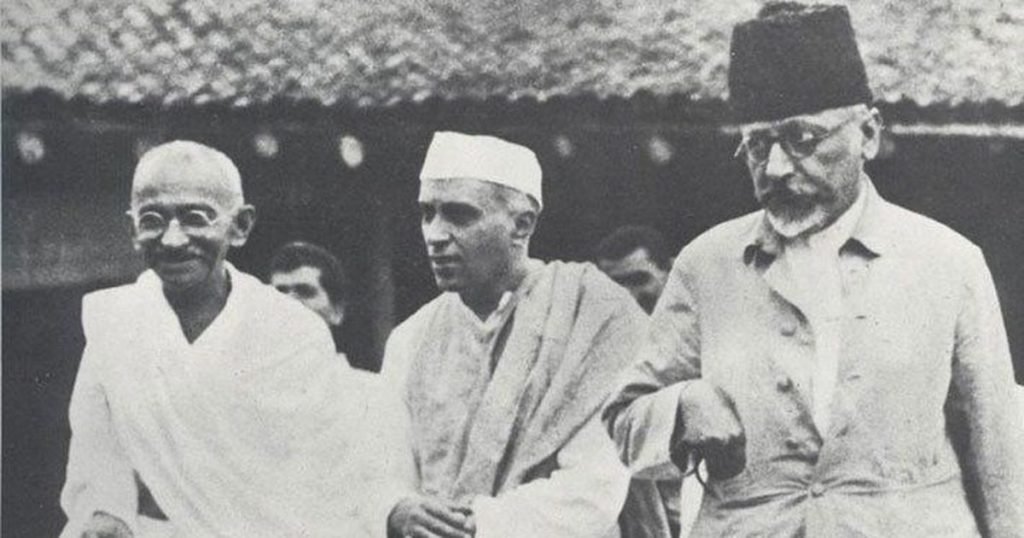

Maulana Abul Kalam Azad (November 11, 1888 – February 22, 1958), born Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin, was one of India’s greatest freedom fighters, thinkers, and educationists. Revered as Maulana Azad, he was a remarkable scholar, orator, and poet whose intellect shaped modern India’s educational foundation. His name Abul Kalam—meaning “Lord of Dialogue”—perfectly reflected his gift for reasoning and debate. The pen name Azad, meaning “free,” symbolized his liberation from narrow dogmas and his lifelong pursuit of truth and progress.

Early Life and Education

Born on November 11, 1888, in Mecca, Maulana Azad came from a lineage of learned Muslim scholars. His father, Maulana Khairuddin, was a Bengali Muslim of Afghan descent, and his mother was the daughter of Sheikh Mohammad Zaher Watri, an Arab scholar. The family returned to Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1890 after years in Mecca.

Raised in an orthodox environment, Azad’s early education focused on traditional Islamic studies under the guidance of his father and eminent tutors. He mastered Arabic and Persian, followed by subjects like philosophy, geometry, mathematics, and algebra. Through self-study, he explored English, world history, and political science, shaping his broad and rational worldview.

A Scholar and Revolutionary

Azad was trained to be a religious scholar, but his intellectual depth and exposure led him to question blind conformity (Taqliq) and embrace reform (Tajdid). Inspired by Jamaluddin Afghani’s Pan-Islamism and Sir Syed Ahmed Khan’s modernist ideas, he traveled widely—to Afghanistan, Iraq, Egypt, Syria, and Turkey—meeting reformists and revolutionaries who deeply influenced his nationalist spirit.

These experiences transformed him into a revolutionary nationalist, determined to unite Indians across religious divides against British rule. Upon returning to India, he met Aurobindo Ghosh and Shyam Sundar Chakravarty, joining Bengal’s revolutionary movement and establishing secret centers across northern India and Bombay.

The Voice of Al-Hilal and Al-Balagh

In 1912, Maulana Azad launched the Urdu weekly Al-Hilal, aimed at awakening political consciousness among Muslims and fostering Hindu-Muslim unity. The journal quickly became a symbol of bold, intellectual resistance. Alarmed by its influence, the British government banned it in 1914.

Undeterred, Azad started another weekly, Al-Balagh, continuing his mission to promote nationalism and unity. It too was banned in 1916, leading to his internment in Ranchi until the end of World War I.

Champion of Hindu-Muslim Unity

Following his release, Azad emerged as a leading figure in the Khilafat Movement, aligning it with Mahatma Gandhi’s Non-Cooperation Movement. His vision was clear—freedom was incomplete without unity among India’s communities. He joined the Indian National Congress in 1920 and, at just 35, became the youngest President of the Congress during its Delhi session in 1923.

Azad was arrested several times for his active role in India’s freedom struggle, including during the Salt Satyagraha (1930). His leadership peaked when he served as Congress President from 1940 to 1946, guiding the organization through the crucial years of World War II and the Quit India Movement.

A Voice Against Partition

Maulana Azad passionately opposed the partition of India, advocating for a federal structure with autonomy for provinces but a shared defense and economy. He envisioned an India where Hindus and Muslims coexisted in harmony. The partition of 1947 deeply saddened him, as it broke his dream of a united, pluralistic nation.

The Architect of Modern Education

After Independence, Maulana Azad became India’s first Education Minister (1947–1958) in Jawaharlal Nehru’s Cabinet. He laid the foundation for the country’s modern education system. His efforts led to the establishment of key institutions such as:

- University Grants Commission (UGC)

- Indian Institute of Technology (IITs)

- Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR)

- Sahitya Akademi and Lalit Kala Akademi

He believed that education should nurture the intellect and character of citizens, not just provide literacy. Under his leadership, National Education Day is celebrated every year on November 11, his birth anniversary.

Legacy and Honours

Maulana Abul Kalam Azad passed away on February 22, 1958, after a lifetime dedicated to the ideals of freedom, unity, and education. In 1992, he was posthumously awarded Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian honor.

His legacy continues to inspire generations—his writings, speeches, and educational vision remain beacons of enlightenment and unity in a diverse India.

***

Pt Jawaharlal Nehru’s Speech in Lok Sabha on the death of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, February 24, 1958)

MR. SPEAKER, SIR: It has fallen to my lot often to refer in this House to the death of a colleague or a great man. I have to perform that sad duty again today in regard to one who was with us a few days ago and who passed away rather suddenly, producing a sense of deep sorrow and grief not only to his colleagues in Parliament but to innumerable people all over the country.

It has become almost commonplace, when a prominent person passes away, to say that he is irreplaceable. That is often true; yet I believe that it is literally and absolutely true in regard to the passing away of Maulana Azad. We have had great men and we will have great men, but I do submit that the peculiar and special type of greatness which Maulana Azad represented is not likely to be reproduced in India or anywhere else.

I need not refer to his many qualities, his deep learning, his scholarship and his great oratory. He was a great writer. He was great in many ways. He combined in himself the greatness of the past with the greatness of the present. He always reminded me of the great men of several hundred years ago about whom I have read in history: the great men of the Renaissance, or in a later period, the encyclopaedists who preceded the French Revolution, men of intellect and men of action. He reminded also of what might be called the great quality of olden days—the graciousness, a certain courtesy or tolerance or patience which we sadly seek in the world today.

Even though we may seek to reach the moon, we do it with a lack of graciousness or of tolerance or of some things which have made life worth-while since life began. It was the strange and unique mixture of the good qualities of the past, the graciousness, the deep learning and toleration, and the urges of today which made Maulana Azad what he was.

Everyone knows that even in his early teens he was filled with the passion for freeing India and he turned towards ways even of violent revolution. Soon after he realized that violence was not the way which would gain results.

Maulana Azad was a very special representative in a high degree of the great composite culture which had gradually grown in India. He, in his own venue, in Delhi or in Bengal where he spent the greater part of his life, represented this synthesis of various cultures which had flowed in and lost themselves in the ocean of Indian life and humanity, affecting and changing them and being changed themselves by them. He came to represent more specially the culture of India as influenced by the cultures of the nations of Western Asia, namely, the Persian culture and the Arabic culture which have affected India for thousands of years. In that sense, I can hardly conceive of any other person who can replace him, because the age which produced him is past. A few of us have some faint idea of that age which is past.

Change is essential lest we should become rooted to some past habit. But I cannot help expressing a certain feeling of regret that with the bad, the good of the past days is also swept away and that good was eminently represented by Maulana Azad.

There is one curious error to the expression of which I have myself been guilty about Maulana Azad’s life and education. Even this morning the newspapers contained a resolution of the Government about Maulana Azad. It is stated that he went and studied at Al Azhar University. He did not do so! It is an extraordinary persistence of error. As I said, I myself thought so. Otherwise, I would have taken care to correct it in the Government resolution. The fact is that he did not study at Al Azhar University. Of course, he went to Cairo and he visited Al Azhar University. He studied elsewhere. He studied chiefly in Calcutta, in the Arabic schools as well as in other schools. He spent a number of years in Arabia. He was born there and he visited Egypt as he visited other countries of Western Asia.

We mourn today the passing of a great man, a man of luminous intelligence and mighty intellect with an amazing capacity to pierce through a problem to its core. The word “luminous” is perhaps the best word I can use about his mind. When we miss and when we part with such a companion, friend, colleague, comrade, leader and teacher, there is inevitably a tremendous void created in our life and activities.

© GreatIndians.org